Post by meatbag on Jun 30, 2010 21:22:09 GMT -8

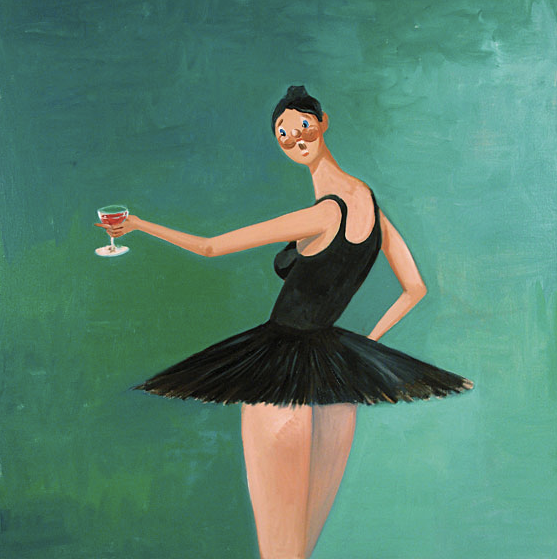

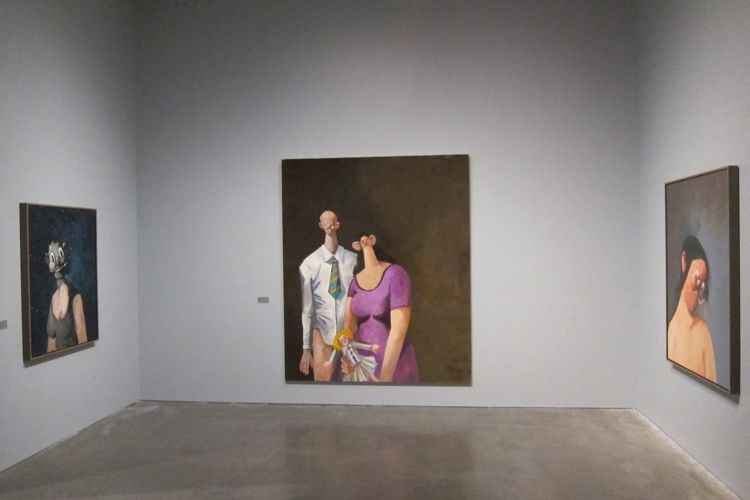

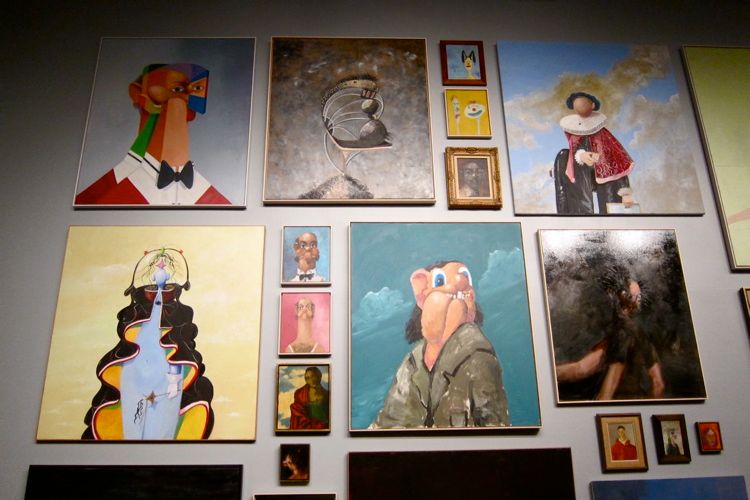

Another really interesting contemporary artist. Love the work he's showing at Art Basel. I really like the simplicity and dark undertones. I'll have to read more up on him. If anyone knows more about him please give it up. Price ranges?

check him at Basel

arrestedmotion.com/2010/06/art-basel-switzerland-2010-part-2/

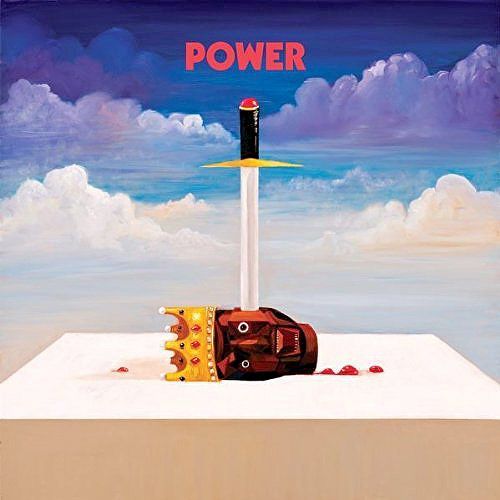

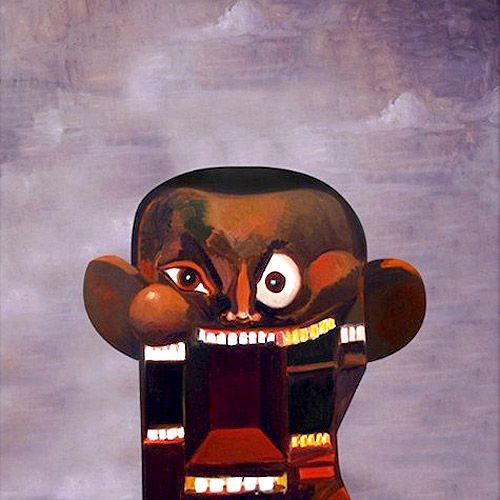

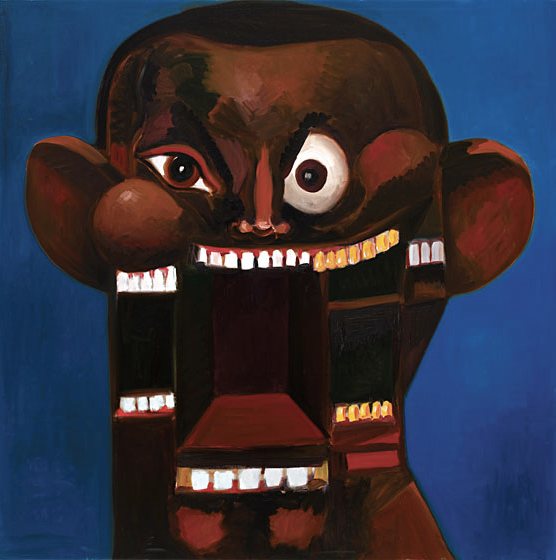

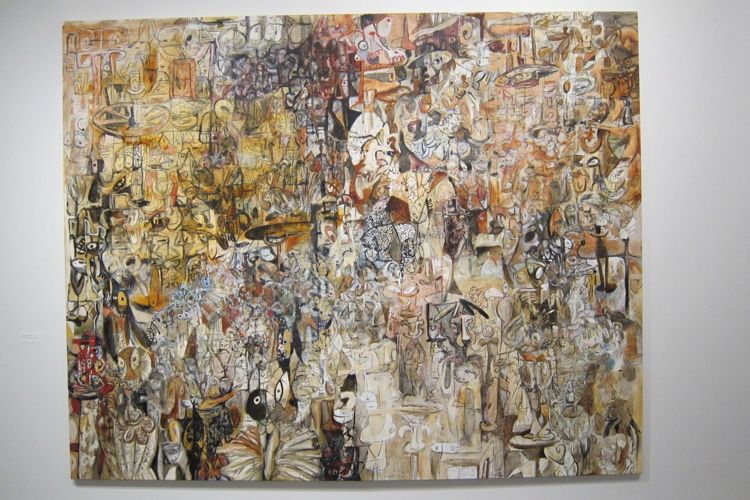

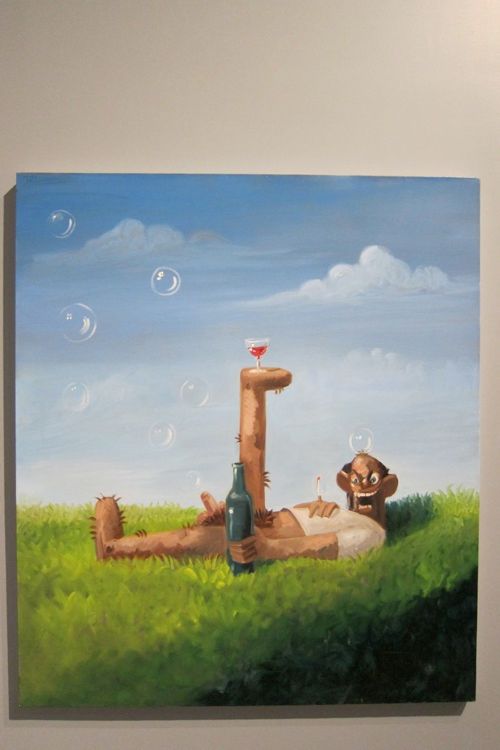

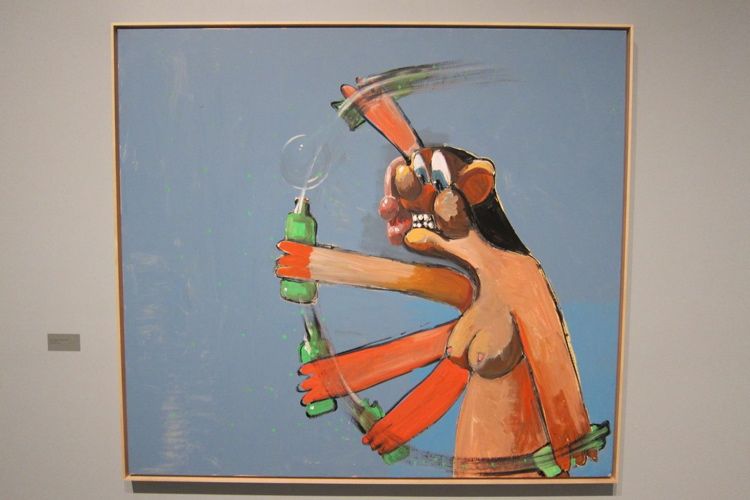

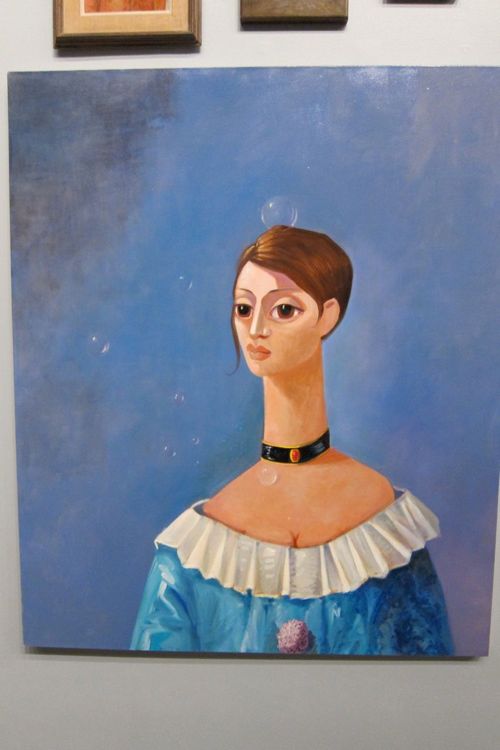

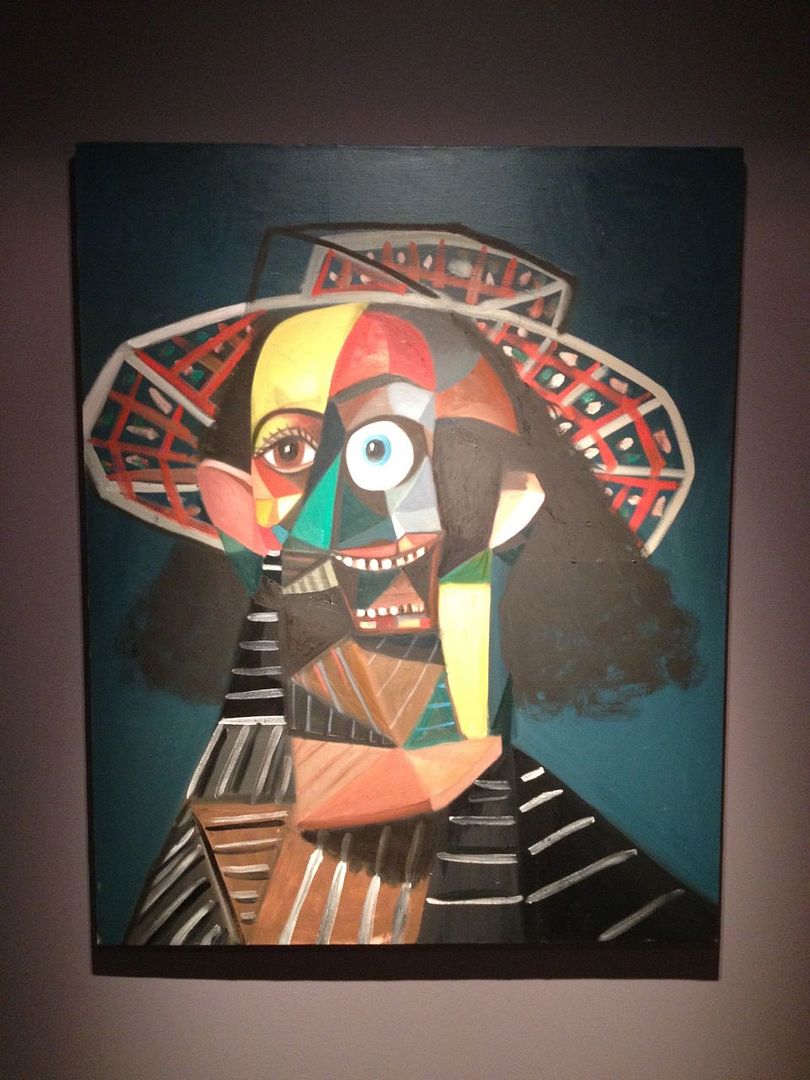

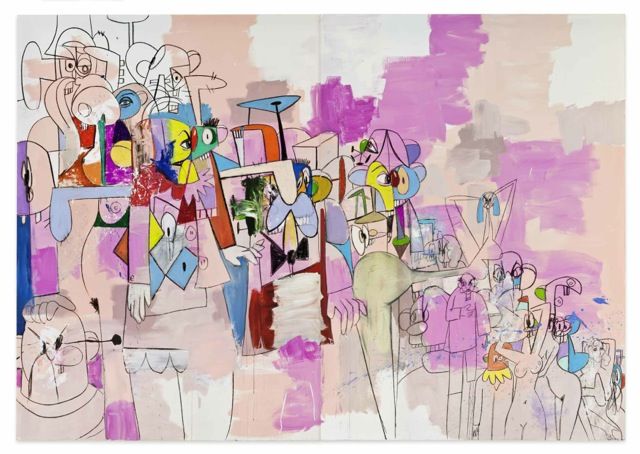

George Condo is a man possessed by visions. A successful Soho artist, he paints what he sees: the "antipodal beings" that dominate his imagination and which he believes to be real. Condo speaks of himself as a sort of receptor who channels images of these creatures which exist but remain unseen by the rest of us.

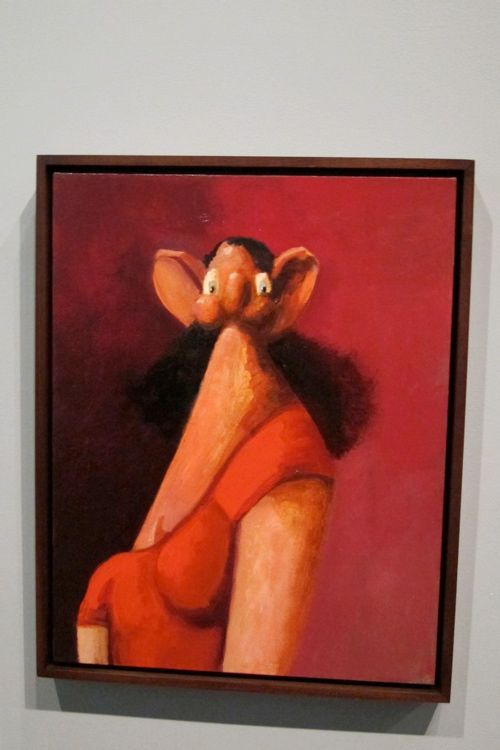

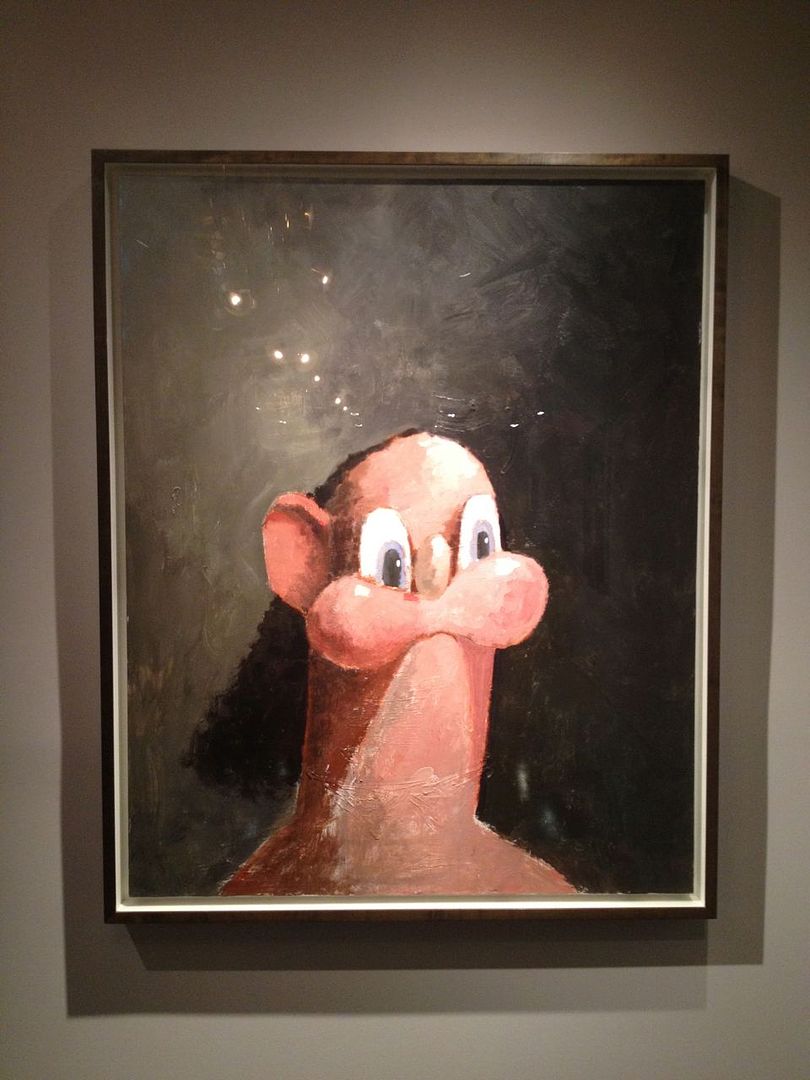

With their bulbous heads, clownish features and enormous eyes, the antipods epitomize kitsch. (How sad to be delusional and see such uninteresting creatures!) Condo paints them in a cartoonish style, all garish colors and shiny surfaces, posed in stiff portraits against flat backgrounds. They look like nothing so much as muppets or troll dolls as painted by Walter Keane, master of the "sad, big-eyed children" genre.

Condo is also a collagist, pasting the faces of old sitcom stars onto reproductions of classical paintings. Whatever small pleasure there is to be gained from the joke of seeing Lucille Ball's head atop the Mona Lisa is blunted by Condo's preposterously inflated claims for the work. "When they stick," he says of the television icons, "they stick permanently. They change the history of art." There's nothing in Condo's smug, smirky tone to suggest that he's joking.

John McNaughton's dreadful documentary Condo Painting matches its subject inanity for inanity. There's no attempt to contextualize the paintings or explore their implications, just ninety minutes of Condo's naked self-regard. Not much happens: we see Condo paint a portrait of the antipod "Big Red" over the course of a year, with interruptions for trips to his boyhood home and to Jack Kerouac's grave, studio visits from Allen Ginsburg and William Burroughs, and goofy playacting on the streets of New York. Condo rants nonstop throughout, keeping up a steady stream of self-aggrandizing patter.

Stealing an idea from the Maysles brothers' Gimme Shelter, McNaughton shoots Condo watching footage of himself painting. In the Maysles' film, the Rolling Stones watch a fan being murdered at their Altamont concert and gradually come to terms with their own culpability. McNaughton's film contains no such revelation. Condo simply watches himself, speaking up now and again to praise his own efforts. Bereft of any wider implications - we learn nothing Condo hasn't already told us about his work - these scenes are embarrassingly masturbatory.

McNaughton is best known for Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. That stark, horrific film was remarkable for its calm good sense. Its protagonist was never mythologized or presented as anything other than a psychotic brute. With no conventional thrills, just scene after scene of bluntly realistic violence, the film put the lie to serial killer chic fantasies like Silence of the Lambs. The rigorous detachment of McNaughton's first film makes his credulous acceptance of Condo's ridiculous schtick that much more puzzling.

McNaughton's failure to build any distance from his subject into the film results in an opaque treatment, dictated by Condo's manic voiceover. He is content with jokey assessments of his own work, so we learn nothing about his life. His failure to reveal himself results in a portrait as flat as his own antipodal paintings.

McNaughton valiantly attempts to disguise the vapidity of his subject - there's not a single idea in Condo's paintings that wasn't explored long ago with greater craft and wit by Duchamp and Warhol - with a barrage of cheesy video effects. Shot in Hi-8 video and transferred to film, Condo Painting utilizes split screens, solarization, traveling mattes and dense superimpositions that suggest nothing so much as an underbudgeted rock video for an '80's retro band. The effect achieved is an unwitting match of form and content: McNaughton's portrait of a logorrheic artist who produces ugly, vacant art is itself wordy, ugly and vacant.

check him at Basel

arrestedmotion.com/2010/06/art-basel-switzerland-2010-part-2/

George Condo is a man possessed by visions. A successful Soho artist, he paints what he sees: the "antipodal beings" that dominate his imagination and which he believes to be real. Condo speaks of himself as a sort of receptor who channels images of these creatures which exist but remain unseen by the rest of us.

With their bulbous heads, clownish features and enormous eyes, the antipods epitomize kitsch. (How sad to be delusional and see such uninteresting creatures!) Condo paints them in a cartoonish style, all garish colors and shiny surfaces, posed in stiff portraits against flat backgrounds. They look like nothing so much as muppets or troll dolls as painted by Walter Keane, master of the "sad, big-eyed children" genre.

Condo is also a collagist, pasting the faces of old sitcom stars onto reproductions of classical paintings. Whatever small pleasure there is to be gained from the joke of seeing Lucille Ball's head atop the Mona Lisa is blunted by Condo's preposterously inflated claims for the work. "When they stick," he says of the television icons, "they stick permanently. They change the history of art." There's nothing in Condo's smug, smirky tone to suggest that he's joking.

John McNaughton's dreadful documentary Condo Painting matches its subject inanity for inanity. There's no attempt to contextualize the paintings or explore their implications, just ninety minutes of Condo's naked self-regard. Not much happens: we see Condo paint a portrait of the antipod "Big Red" over the course of a year, with interruptions for trips to his boyhood home and to Jack Kerouac's grave, studio visits from Allen Ginsburg and William Burroughs, and goofy playacting on the streets of New York. Condo rants nonstop throughout, keeping up a steady stream of self-aggrandizing patter.

Stealing an idea from the Maysles brothers' Gimme Shelter, McNaughton shoots Condo watching footage of himself painting. In the Maysles' film, the Rolling Stones watch a fan being murdered at their Altamont concert and gradually come to terms with their own culpability. McNaughton's film contains no such revelation. Condo simply watches himself, speaking up now and again to praise his own efforts. Bereft of any wider implications - we learn nothing Condo hasn't already told us about his work - these scenes are embarrassingly masturbatory.

McNaughton is best known for Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. That stark, horrific film was remarkable for its calm good sense. Its protagonist was never mythologized or presented as anything other than a psychotic brute. With no conventional thrills, just scene after scene of bluntly realistic violence, the film put the lie to serial killer chic fantasies like Silence of the Lambs. The rigorous detachment of McNaughton's first film makes his credulous acceptance of Condo's ridiculous schtick that much more puzzling.

McNaughton's failure to build any distance from his subject into the film results in an opaque treatment, dictated by Condo's manic voiceover. He is content with jokey assessments of his own work, so we learn nothing about his life. His failure to reveal himself results in a portrait as flat as his own antipodal paintings.

McNaughton valiantly attempts to disguise the vapidity of his subject - there's not a single idea in Condo's paintings that wasn't explored long ago with greater craft and wit by Duchamp and Warhol - with a barrage of cheesy video effects. Shot in Hi-8 video and transferred to film, Condo Painting utilizes split screens, solarization, traveling mattes and dense superimpositions that suggest nothing so much as an underbudgeted rock video for an '80's retro band. The effect achieved is an unwitting match of form and content: McNaughton's portrait of a logorrheic artist who produces ugly, vacant art is itself wordy, ugly and vacant.