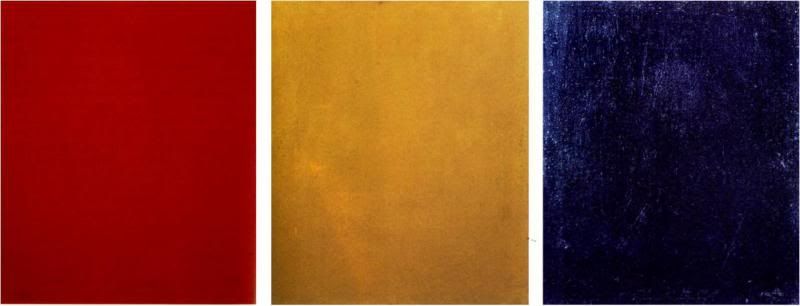

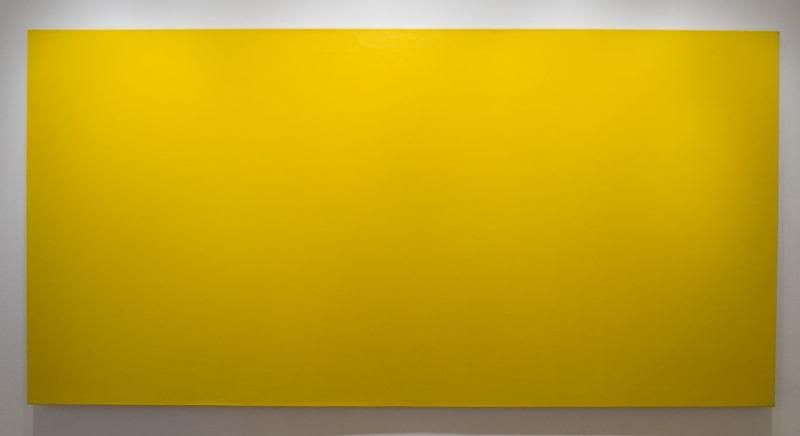

Seeing this instantly makes me think of the history of the monochrome in art. I don't go back as for as the 1880's, which I've heard is when one of, if not the first, monochrome was presented, but I've read back to 1921 and Alexander Rodchenko's 'Pure Color', of which he later said, " "I reduced painting to its logical conclusion and exhibited three canvases: red, blue, and yellow. I affirmed: it's all over." Kind of simultaneously arrogant, nihilistic, and short-sighted, yes?

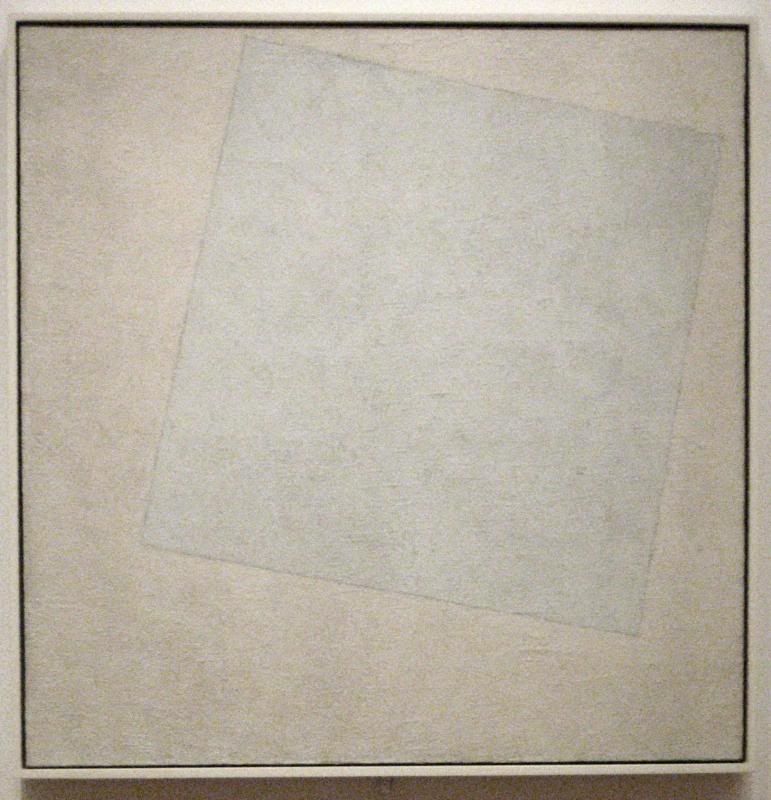

Also of the time period(actually slightly earlier), and the same location, was Kazimir Malevich's 'White on White'(1918) which resides at MoMA. While not a true monochrome, it does have a 'subject'(as opposed to solely an 'object') however minimal, it has to be included as a famous example. Also, it has been argued, successfully for me, that it is in fact the depiction of a monochrome surround by white space.

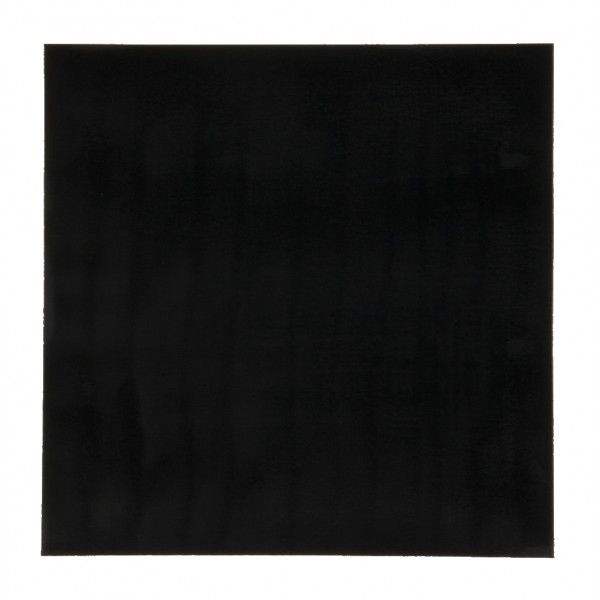

'White on White' was an extension of an earlier, and equally famous work, 'Black Square on White Field'(1915). This work is obviously not a monochrome, but represents one avenue of what led to monochrome, namely geometric abstraction. It also highlights that, at the time, these were radical men doing radical things. Like the Impressionists at the French salon shows in the 1800's, this work was radical, subversive, and an attempt at social change via art.

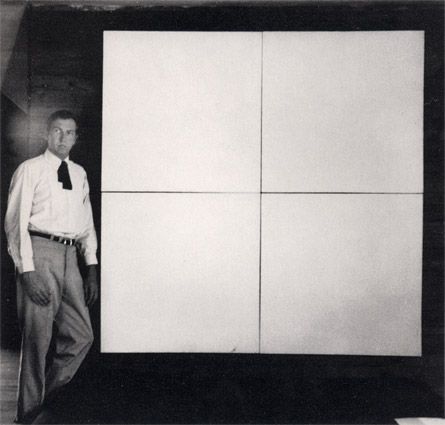

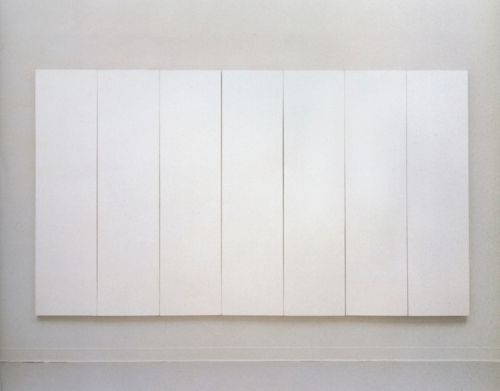

Now, there may be a gap between these Russian explorations and 1951, or the gap may be my own fault for not having read enough. Either which was, my personal next focus with regard to the monochrome is Robert Rauschenberg's 1951 white paintings.

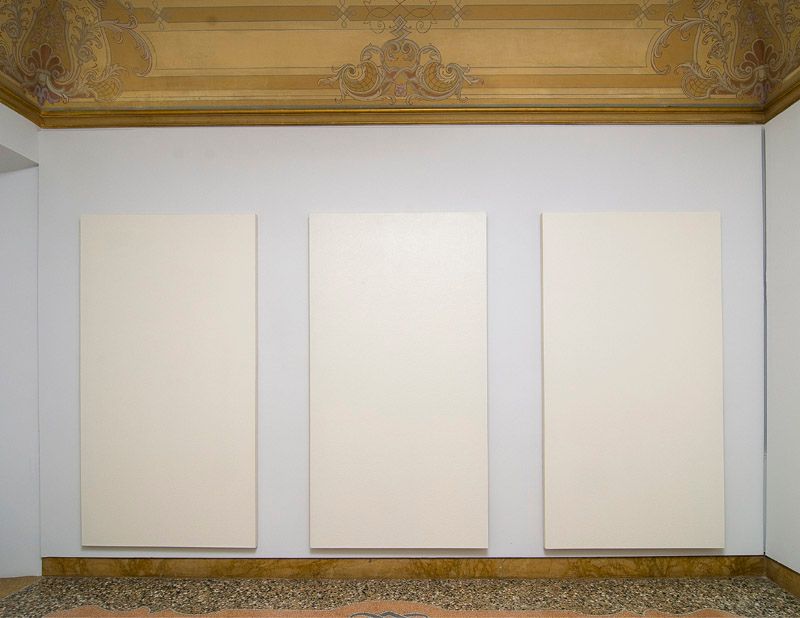

Rauschenberg's goal with these, like many minimalists and, to an extent later painters like Robert Ryman, was to 'capture' the ambient environment on the painting. Every shadow, every speck of dust, every lighting element adds to the experience of these paintings. They are screens, capturing what is around and sensitizing the viewer to the viewing environment.

Rauschenberg went on to make black paintings and red paintings, but they strayed further and further from the 'purity' of the white paintings and fidelity to the monochrome, incorporating newspaper, found objects, etc. into their construction. They were basically a segue from the white paintings to Rauschberg's later, much celebrated combines such as 'Canyon'(1959), now on display at MoMA:

Then you get to the glorious 1960's. An era of absolutely amazing art and ideas and, perhaps, the last 'pure' era of art prior to the infamous Scull auction of the early 1970's wherein fresh, contemporary art went from basically non-sellable and worth little(with an exceptionally small collector base) to very much a commodity.

First up is Ad Reinhardt, whose 'abstract paintings' at first glance appear to be dark black monochromes and very much embrace the nihilist 'last painting' ethos often associated with monochrome. After extended viewing, once your eyes adjust, it becomes clear that Reinhardt's paintings are not monochromes, but subtly-colored geometric forms in various dark tints of red, blue, green, etc.

Reinhardt, in 1961, described his 'abstract paintings'/black paintings, "A square (neutral, shapeless) canvas, five feet wide, five feet high, as high as a man, as wide as a man's outstretched arms (not large, not small, sizeless), trisected (no composition), one horizontal form negating one vertical form (formless, no top, no bottom, directionless), three (more or less) dark (lightless) no–contrasting (colorless) colors, brushwork brushed out to remove brushwork, a matte, flat, free–hand, painted surface (glossless, textureless, non–linear, no hard-edge, no soft edge) which does not reflect its surroundings—a pure, abstract, non–objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting—an object that is self–conscious (no unconsciousness) ideal, transcendent, aware of no thing but art (absolutely no anti–art)." He indicated that this work, with a strong spiritual connection to Chinese painting and philosophy, was an attempt to, ""a pure, abstract, non-objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting—an object that is self-conscious (no unconsciousness), ideal, transcendent, aware of no thing but art."

Cory D'Augustine, an amazing teacher/lecturer/artist/conservator out of NYC(MoMA, Guggenheim, etc.) goes in detail with regard to Reinhardt's technique:

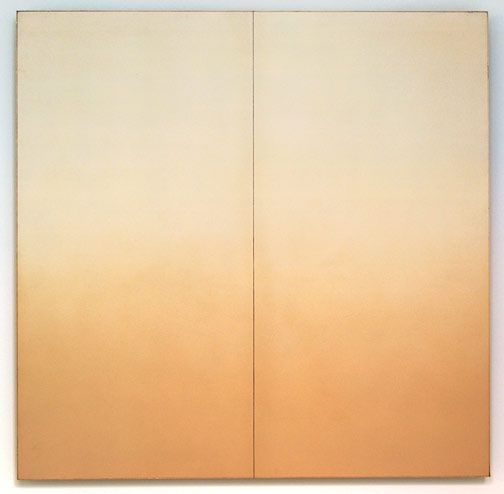

www.moma.org/videos/embed/129/688Reinhardt videoThis leads us to the figure that I see most connected to the current work by Darmstaedter,namely Robert Mangold. Mangold's early work of the mid-1960's share similarities with the current painting. Especially when one considers the color palette. Mangold's early works were known, even infamous, for his use of the colors of industry. Revolting, banal, insidious colors of industry of the 1960's. 'Paper bag brown'? Check. 'File cabinet grey'? Check. 'Manilla envelope tan?' Check. Basically, the daily commerce that surrounds us all.

One could also now discuss people like Brice Marden, whose monochromes of the 1960's had an almost magical, soul-absorbing power due to their surface and Marden's unique beeswax/pigment/turpentine blend. But, I think a more important focus is Olivier Mosset and his exploration, beginning in the 1970's, of the monochrome and returning to its early 1900's, Rodchenko/Malevich, social radicalism.

I think this mini-review, in discussing the current work by Darmstaedter, highlights an important aspect of monochrome in that it illustrates my favorite Duchamp quote, "The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act" If you bring art history knowledge to a monochrome, if you look beyond 'at' and toward 'why', the paintings take on meanings and dimensions not immediately evident in their 'blank' surfaces.

These artists, and there work, require you to move beyond the narrowness of 'subject' of painting, toward an embracement of the 'object'(using the 'end toward which a specific action is directed; goal; purpose) of painting in general and any specific painting. They are, with abstract painting, not the same thing. They are also the very thing at a museum that separates the art fan from the passing observer. The passing observer tends not to look for anything beyond their retinal scope. 'Just the facts ma'am.' This reductionist view turns the monochrome into a canvas with some paint on it.

But, as the history of the monochrome shows, there has long been, most definitely, an 'object' to these paintings. From Rodchenko/Malevich and a radical social agenda, to Mosset picking that agenda back up some 60 years later and beyond, there have been reasons for the monochrome.

What is the reason for Darmstaedter?

I think it is also important to look at the use of the water dispenser in this work. For me, it presents in-line with my understanding of tenets of dada. I see the 'art-ization' of readymade objects. I even see a sort of echo of Rauschenberg's journey from pure, white-painting monochrome, through black monochrome and their incorporation of newspaper, the the red paintings becoming even less pure monochrome with nails and various other inclusions, to the combine - the amazing painting/sculpture hybrids.

I mean, is this current work a painting? Yes and no. Is it a sculpture? No and yes. Is it artist's hand? Yes and no. Is it 'artist's head'? No and yes. Is the artwork primarily a manifestation of its physical components, or is it conceptual underpinnings? Both and neither.

What is this and why? Are there any better questions that art can leave you with?